Standing stock still on a Tenderloin sidewalk in chilly darkness, heroin needles at his feet and sirens keening in the distance, Baron Feilzer’s world narrowed to the face in front of him.

Looking back at him for the first time in seven years and what seemed like a lifetime ago was his brother, Tyson.

Tyson’s eyes held the thousand-yard stare of a man tortured by seven years of heroin and homelessness. Baron’s eyes were misty. Relief and sadness warred in his head, but Baron had just one clear thought: “What do I do now?”

Baron reunites with Tyson after seven years.

(Nick Otto / Special To The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)

It flickered for only an instant. Baron had prepared for this moment. He knew what to do.

“Want to go for a ride?” he asked his brother.

“Yeah,” Tyson said. They got in the car.

The hunt for Tyson Feilzer began about a week before that moment on the sidewalk.

Baron, 38, got a call at his home in Ohio from a relative who’d just read a story in The Chronicle about homeless people along the Embarcadero. It quoted 40-year-old Tyson saying he thought putting a new shelter on the waterfront was “a great idea.”

His picture ran with the April 14 story. There was no doubt it was Baron’s brother. Baron called The Chronicle.

“We haven’t seen him in more than seven years, not since my wedding, had no idea where he was, and when I saw that photo it hit me hard,” Baron said. “I figured he was probably homeless but was hoping maybe he wasn’t. I know I have to come get him.”

The Chronicle had come upon Tyson near a parking lot where a Navigation Center is being proposed. Seated on a piece of cardboard in the bright sun, he was thoughtful. Regretful.

“I’ve been out here for a lot of years,” Tyson said quietly. “If I could get a place for a few months, I could get back to a real life.”

Sleeping on the street in San Francisco, addicted to heroin and methamphetamine, was an unlikely fate for a man who grew up the privileged son of an accountant and a real estate agent in the upscale suburb of Danville.

Tyson (left) and Baron attend Baron’s wedding in 2012 with their father, Jim Feilzer.

(Courtesy Baron Feilzer 2012 | San Francisco Chronicle)

At Monte Vista High School he played football, breezed through classes and was a popular jokester. After graduation he went to Chico State University. He didn’t graduate but started a career as a mortgage broker and salesman.

Baron, younger and quieter, was on the wrestling team in high school and earned a master’s degree in management at Penn State University. Today he’s an operations manager at an industrial plant in Peninsula, Ohio.

Both drank a bit too much as young men. Baron overcame it. Tyson didn’t.

When the recession hit in 2008, Tyson wound up living with his grandmother in Pleasant Hill. Joblessness set in, and his 94-year-old grandmother fell, broke her hip and died. The house she was in got sold, and Tyson had to leave. After a couple of temporary jobs in the East Bay, he went broke, with no place left to live. So he hit the streets.

Tyson went to San Francisco, and stayed. The booze habit degenerated into heroin and meth. Life became a desperate daily hunt for dope and a place to crash. Petty crimes — breaking into cars, drug busts — led to a few months in jail here and there.

Embarrassed at being on the street, he broke off with everyone. He stayed disconnected so long he lost track of everyone — including his family.

“I’d never even seen heroin before I was on the streets, and just smoked it for the first two years trying to tell myself I could control it,” Tyson said. “Then I started injecting. And then I was lost.

“I am lost.”

After seeing Tyson’s picture in the paper, Baron booked a spot in a residential detox center in the Sierra foothills. The next day, he started a GoFundMe page to raise the $40,000 needed to pay for a 45- to 90-day rehab program. Then he booked a flight to San Francisco. He asked the Chronicle reporter to lead him and an intervention specialist he hired through the streets to look for Tyson.

“I’m either coming to take him to rehab, or to say goodbye if that’s what he wants,” Baron said. “But I need help finding him. I have to. He’s my big brother.”

At 11 a.m. on April 26, just an hour after Baron landed at SFO, he, the reporter and the interventionist, Vicki Lucas, set out on the Embarcadero. The search started at the spot where Tyson had sat just days before. It continued along the waterfront, up Market Street and into the Tenderloin. They showed photos of Tyson to everyone who would look.

The trail would stretch 6 miles over nearly 12 hours.

-

Lucas and Baron ask Shawn Swanson, better known as Seven, whether they have seen Tyson.

Lucas and Baron ask Shawn Swanson, better known as Seven, whether they have seen Tyson.

Photo: Nick Otto / Special To The Chronicle

Caption

Close

Lucas and Baron ask Shawn Swanson, better known as Seven, whether they have seen Tyson.

Lucas and Baron ask Shawn Swanson, better known as Seven, whether they have seen Tyson.

Photo: Nick Otto / Special To The Chronicle

Every time Baron bent low toward a sleeping shape on the sidewalk, the grass or a bench, he hoped. “Hi, how are you doing? Got a second?” he said.

Each time, his heart skipped while he waited for a hand to reach out from beneath a sleeping bag or blanket and unveil a face. Each time, when it wasn’t Tyson’s, Baron’s heart fell. He’d show the picture, ask, “Have you seen this guy? He’s my brother,” then move to the next shape on the street.

It took about a dozen queries before he got his first lead.

“Yeah, I know that guy, he’s a good dude,” said a 47-year-old homeless man with a neatly groomed salt-and-pepper beard, sitting on a concrete wall facing the Ferry Building. He gave his name only as T. “He’s got some wisdom to him.”

Baron’s face lit up. “Where can we find him?”

“Well, he’s kind of a loner, real smart, but sleeps in different spots. You’ll have to look around.”

Baron nodded, silent.

“You miss your brother?” T asked.

“Yeah.”

“Keep looking. He needs you,” T said. “Me? My family passed away. Nobody’s looking for me. And you stay out here long enough, like me, it gets deep. When s— happens to you it’s like a tattoo. It never leaves. It’ll kill you.

“But Tyson,” he said, patting his chest, “at least he has you. Go find him.”

More stops, more tips. Tyson slept on Second Street, along the Embarcadero, maybe at a rundown hotel in the Tenderloin, maybe near a post office. He’d been seen days ago, weeks ago, years ago.

Then came the best lead: Tyson liked to shoot up at an unsanctioned injection center on Turk Street in the Tenderloin. The group set off.

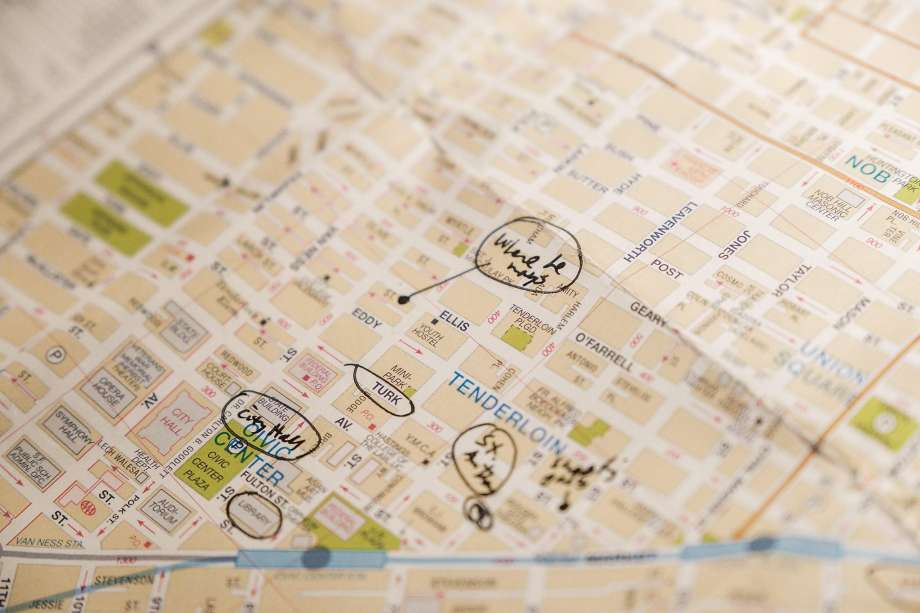

Baron and Lucas document their search for Tyson on a San Francisco map.

(Nick Otto / Special To The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)

There, sitting outside the center with a dozen other addicts was a guy called Seven, a middle-aged, longtime homeless man otherwise known as Shawn Swanson.

Seven lurched to his feet when he heard Tyson’s name.

“You have to find him, man, you have to find him,” he said. “Tyson has been convinced beyond what normal people usually are that his family is looking for him. He’s been saying that for a few years now. Lots of people are stuck out here.

“I lost faith in it; my family’s done with me. But Tyson? He needs to be with people who love him, not brother junkies. He’s smart. He just needs the chance.”

Baron and Lucas took out one of the photos they carried and wrote their phone numbers on it. They gave it to Seven.

“Call us, please, if you find him,” Baron said, shaking Seven’s hand.

“You bet, brother,” Seven said.

At 10:15 p.m., he did.

At 10:36, Baron stood in front of Tyson on Larkin Street.

More than 40,000 people are reported missing every year in California, according to the state Department of Justice. San Francisco counted 2,155 chronically homeless people — those, like Tyson, who have lived outside for more than a year with debilitating factors such as addiction or mental illness — in its latest one-night survey in 2017.

Related

-

Homeless people excited but skeptical about idea for waterfront -

Nearly half of older homeless people fell into trouble after 50

Off and on over the past few years, Baron had called soup kitchens throughout the Bay Area, filed missing person reports, and found records of Tyson’s short jail terms in the Bay Area for petty theft and drug possession. But he could never pinpoint where he was. That’s not unusual, drug rehab specialists say.

People lost to dope and the gutter exist under the radar. San Francisco has vigorous street counseling outreach teams but can’t help unless a homeless addict accepts an offer of shelter or programs. Tyson didn’t. He was embarrassed. He’d lost almost all hope.

“When you’re using, some part of you thinks you still have control, but you don’t,” said Thomas Wolf, 49, a Salvation Army case manager in San Francisco addicted to heroin in the same Tenderloin streets as Tyson before being helped into rehab by his brother more than a year ago.

“I smoked heroin right where Tyson used, and if you’re not in a rehab center to get clean, you won’t deal with the underlying issues,” he said. “You’re not going to get clean on the streets.”

It’s not clear just what issues drove Tyson to the needle and the pavement. His father, Jim Feilzer, who lives in Missouri, suggested a few possible factors: Baron was ill as a toddler and required more attention, the parents divorced when the kids were young, he partied too much in high school, he started drinking as a teenager, sorrow over his grandmother’s death.

“I can’t say what makes people do what they do,” said Feilzer, 71. “That is all in the past. What I know is that Baron has a good frame of mind for what he wants to do for Tyson. Tyson probably doesn’t think anyone cares. But they do. We all love him.”

Tyson had just finished scrounging women’s clothing out of a dumpster to sell on Larkin Street when Seven strolled up to him that Friday night. He called Baron, who raced over from his hotel room, stepped out of his car and walked over.

“Hey Baron,” Tyson said, matter-of-factly, masking the shock. He tried to shake Baron’s hand, but his brother pulled him into a tight hug.

Then came that moment of staring into each other’s eyes. They left the stuff Tyson was hawking and drove to Baron’s hotel.

Minutes later, Tyson was sitting on the first clean bed he’d seen in longer than he could remember.

Lucas gave him a few minutes to think and make a little small talk. Then she asked: “How would you feel about getting detoxed and going home with Baron to meet your niece?”

In any intervention, this is a key juncture. Some addicts say OK but ask to take care of some business first, which almost always means they’ll disappear as soon as they hit the door. Others just say no. Tyson had tried briefly to kick dope twice before and failed — typical, considering most addicts need several attempts for one to stick.

Sitting in the hotel room with Baron and Lucas, he didn’t hesitate.

“OK, yeah,” Tyson said, his head bowed. Then he looked up.

Baron Feilzer (left) reunites with his brother, Tyson Feilzer, after reading about him in The Chronicle.

(Nick Otto / Special To The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)

“I hate being homeless,” he said, his voice flat and low. “I could have gone to Oakland or some other place, but I stayed here in San Francisco because I wanted you to be able to find me. I just felt like my family would come for me someday.”

He scratched at a nickel-sized abscess on his right forearm. “This is what happens when you’re on the street,” he said. “You get sick. You get infections. … You get pushed around. People look right through you.

“It’s an earned reputation,” Tyson said. His eyelids sagged.

“Growing up in Danville definitely didn’t prepare me for this kind of life.”

Baron pulled out his phone, a sheaf of photos and a piece of paper. “I have a letter here from Dad,” he said. He sat next to Tyson on the bed, handed over the photos — of Tyson as a baby, of family vacations — and began to read:

I’m writing this letter because I love you. When you were born it was the happiest day of my life. I regret you did not hear that enough.

Baron wiped his eyes. Tyson fingered the photos with street-grubby hands, staring. Listening.

Drugs and alcohol have not helped you, Tyson … our family wants you back. You have a life worth living. Please choose to live it. I know you can do this.

Baron finished reading, and the brothers sat silent for a long moment. “Tyson, you know how hard it was for Dad to say that kind of stuff.” Tyson nodded, eyes to the floor. “He really cares.”

Baron held out his phone. He pulled up a video of his 3-year-old daughter, Penny, saying hello to the uncle she’d never met. By now Baron was weeping.

“When you come home with me after you do rehab, you’re going to have to get used to Disney movies,” Baron told Tyson. “You haven’t seen ‘Frozen,’ have you?”

Tyson smiled, his first that night. “No, I haven’t,” he said, looking up.

“Well, you’re going to have to,” Baron said. “About a million times.”

Tyson slept in the bed that night, Baron on a foldout nearby. In the morning, a freshly showered Tyson ate breakfast and was ready to go. But he hadn’t shot up for several hours and started to get dope-sick — the nausea of early withdrawal. So he did what so many people headed to rehab do.

A cousin had driven in from the Central Valley to take them to the detox center in the Sierra, and the entire group drove to the Tenderloin. Lucas got out with Tyson, and in five minutes he’d scored a $10 strip of Suboxone — a withdrawal medication for heroin addicts — from a dealer. The aching went away.

Two and a half hours later, he was in detox and preparing to head to rehab at the Oxford Treatment Center in Etta, Miss.

On the sidewalk on Larkin Street, where the hunt for Tyson had ended but his rescue had only begun, Seven and the half-dozen pals who were there when Baron showed up took stock of what they’d seen. Two days later, Seven wrote a note to Baron:

We are all so proud of Tyson. Change is scary and it is something most of us avoid. He’s facing this head on. And more importantly we love him unconditionally, high or sober in stable housing or not.

A lot of us deal with guilt and shame because we let a family member down or disappointed them when our addictions caused us to slide off the road. We don’t want him feeling that way about us.

We’re blessed to know him and experience life with him. He’s a great man.

Baron flew home to Ohio after the weekend, where he and his wife are making accommodations for Tyson in their home. They know nothing will be easy.

“I think he’s gonna do it,” Baron said. “I think he’s learned the lessons he needed to learn.”

Tyson seemed to feel the same way. In the hotel room the night he was found, he mused, “There have been so many bottoms it boggles the mind.

“Why did I have to suffer through days without being able to get out of the rain? Dope sick? Being a heroin addict? I don’t know what God has in mind for me, what the point is.

“But I’m going to try to find out,” he said. “Thank God Baron came looking for me.”

“I love you,” Baron said.

Tyson nodded. “Yeah,” he breathed.

Kevin Fagan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kfagan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @KevinChron

Article source: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Once-homeless-now-found-Danville-native-13817848.php